1906-1909

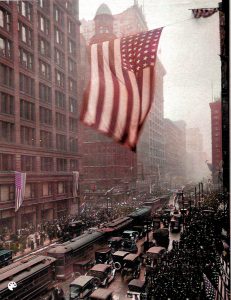

New York City and Chicago

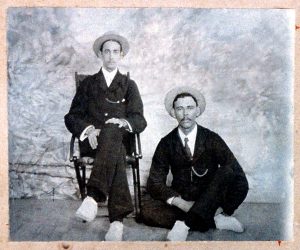

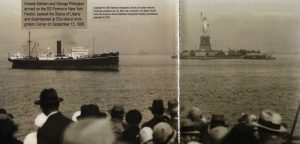

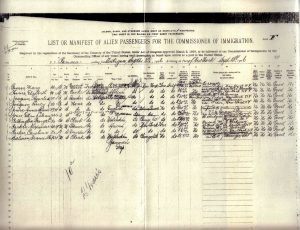

The entire West Indies had been suffering from an economic depression and the Salmon family in Antigua struggled with the limited money that family members could raise. In 1906 at 18 yrs of age, Horace decided to leave his job in a St. Johns mercantile store and go to the USA where they heard that people were doing better. His best friend, George Pilkington, had family already living in Chicago, so the two of them saved up to buy First Cabin passage ($58.00 each) on the SS Parima and sailed to New York City. That ship’s Manifest for September 13, 1906 lists George C. Pilkington (age 22) as No.7 and Francis H. Salmon (age 18) as No.10, whose nationality lists “West Indian” and final destination as “Chicago.” A Certificate of Authenticity can also be accessed here. They were processed in the Ellis Island Immigration Center and then caught a train to Chicago.

Marshall Fields

It would be so nice to know just how Horace landed the job in the Jewelry Department of Marshall Fields Department Store. Whether he got a recommendation through a friend of the Pilkingtons, or simply walked in at just the right moment and interviewed with someone who saw a match for that job in his previous six year employment in St. Johns. At any rate, Horace earned $9.00 per week and sent $3.00 of it back to his family in Antigua. During 1907, the average wage in the USA was 22 cents/hour or $8.80/week ($458/year). There were only 8,000 cars in the U.S. and only 144 miles of paved roads. That year, only 6 percent of all Americans had graduated from high school. Horace’s schooling at English Harbour in Antigua had ended with the 3rd grade.

Horace rented a room in an unheated attic and walked or rode the tram to work. For someone who had lived all his life in the tropics, bitter cold winter and snow was a new challenge. Below zero nights meant going to bed wearing several layers to hold in his body warmth including a night cap. A potty under his bed was handy as an alternative to a trip downstairs for the nighttime need to relieve one’s bladder.

Shaving each morning in the communal bathroom meant a trip beforehand down to the kitchen to heat some water on the coal stove and bringing it up in a little basin. Stropping the open-out straight razor on a leather strap to sharpen the blade was an important part of the ritual. A decade later the safety razor was invented with replaceable blades. Preparing his work clothes included ironing a starched white shirt and pressing his trousers to be sure to have a neat pleat down the front. Getting to work with neatly shined shoes meant wearing goulashes during the winter and rubbers on rainy summer days. Needless to say, the morning routine required a couple of hours in order to report promptly for the 10:00am opening of the store.

Marshall Fields was a colossal structure that covered an entire city block in downtown Chicago. Going upstairs to his Jewelry Department involved a wide stairway with landings midway, or waiting on the slow elevators and asking an operator to stop on your floor. Escalators that were just being invented, wouldn’t be added until years later.

Every morning, dressed in a suite with white shirt and tie, Horace took the tram down to State Street and entered the main floor of the atrium. Avoiding the employees gathered around the doors of the elevators, he hurried up the broad stairway often taking two steps at a time with his long legs. He hung his overcoat (or raincoat or light summer coat) and his hat in the workroom behind the counters, put the things he was carrying into his cubbyhole, and looked into the long mirror on the wall to be sure his hair was all right and his tie was on straight. Checking in with his supervisor, he got instructions for the day, wiped finger prints off the display cases, and promptly at 10:00am the bell sounded and customers entered the store and made their way up to places like his Jewelry Department. Horace Salmon repeated this routine day after day, month after month, six days per week. The store was closed on Sundays.

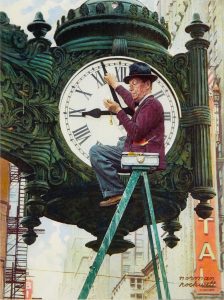

On that busy corner in downtown Chicago hung the renowned green clock. Whether while walking by or when looking out a window of a passing trolley car, people looked up to see the time. In a world of windup clocks and pocket watches, it helped with coordination of time pieces for an entire city. And that’s where Horace worked. Right at the center of it all. Rockwell’s painting, “The Clock Mender,” shows a meticulous repairman sitting on a high step-ladder relying on his trusty old pocket watch to set the time on the famous clock at Marshall Field’s store. It appeared on the cover of the November 3, 1945 issue of the SaturdayEvening Post.

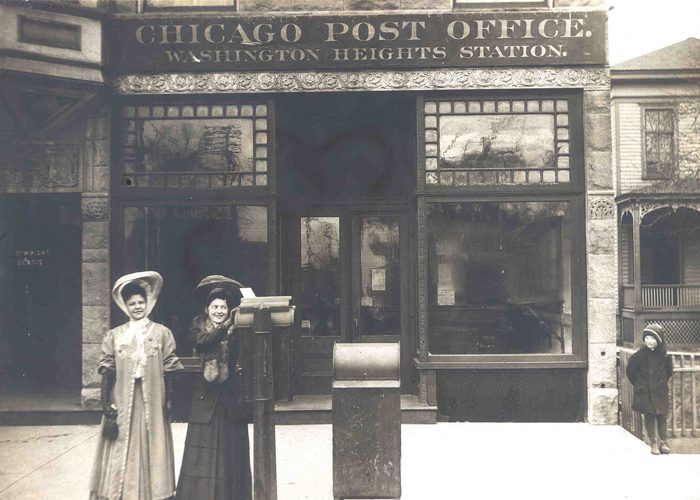

Ella Salmon Follows Horace

A short time after Horace arrived in Chicago, his older sister Ella followed in his footsteps. Elizabeth Pamela Harmon Salmon had been born April 11, 1886 at Richmonds Estate and in her teens, also went to work to provide for herself and the family in St. Johns. She became a hair dresser, a trade that she was able to utilize in America. Notice the braided hairdo in her immigrant portrait. When 20 years old, Ella called upon a dear friend named Mother Martin to accompany her journey. Out of the generosity of her heart, Mother Martin gave Ella a watch with an “M” engraved on the lid. City living (like riding the trolleys) required a new timeliness and she needed to have her own time piece. The model was a curiosity to many at the time because it was designed as the first “self-winding” watch. From 1906 to 1909, Ella lived with a Mrs. Jacobson whom she called “Mother J.” Ella and Horace were a great support to one another in their adventures into this new land.

After braving three winters in the Windy City (Chicago), Horace learned that the Fred Harvey Company was looking for a jewelry and rug sales person for their new Indian Stores at railway stations in New Mexico and Arizona. In 1909 he moved to the dry and warmer climate of Albuquerque, New Mexico. And another of his dreams came true: to get to explore America’s South West. The story continues in the next chapter.

Additional images: